Journal:An evaluation of regulatory regimes of medical cannabis: What lessons can be learned for the UK?

| Full article title | An evaluation of regulatory regimes of medical cannabis: What lessons can be learned for the UK? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids |

| Author(s) | Schlag, Anne K. |

| Author affiliation(s) | DrugScience, King's College |

| Primary contact | Email: anne dot schlag at kcl dot ac dot uk |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Volume and issue | 3(1) |

| Page(s) | 76–83 |

| DOI | 10.1159/000505028 |

| ISSN | 2504-3889 |

| Distribution license | Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/505028 |

| Download | https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/505028 (PDF) |

|

|

This article should be considered a work in progress and incomplete. Consider this article incomplete until this notice is removed. |

Abstract

This paper evaluates current regulatory regimes of medical cannabis using peer-reviewed and grey literature, as well as personal communications. Despite the legalization of medical cannabis in the U.K. in November 2018, patients still lack access to the medicine, with fewer than 10 NHS prescriptions having been written to date. We look at six countries that have been at the forefront of prescribing medical cannabis, including case studies of the three largest medical cannabis markets in the European Union: Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. Canada, Israel, and Australia add global examples. These countries have a more successful history of prescribing medical cannabis than the U.K. Their legislation is outlined and number of medical cannabis prescriptions provided to give an indication of how successful their regulatory regime has been in providing patient access. Evaluating countries’ medical cannabis regulations allows us to offer implications for lessons to be learned for the development of a successful medical cannabis regime in the U.K.

Keywords: medical cannabis, patient access, legislation, regulation

Introduction

Cannabis has a long history, being one of the oldest medicines and having been used for millennia.[1] However, today’s medical cannabis, used for a broad range of indications, only has a short past, requiring novel regulatory regimes to ensure the safe and effective use of cannabis as medicine. In most countries, the provision of medical cannabis has evolved over time, often in response to patient demand and/or product developments. International licensing laws regarding the safety and quality of cannabis medicines vary greatly.

In the U.K., medical cannabis was legalized and made available under special license through the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in November 2018 as a result of public controversy and campaigning. Nevertheless, since that time, only a very small number of patients with a limited range of conditions have been provided treatment within the National Health Service (NHS), meaning that medical cannabis remains inaccessible for most patients in need. Physicians are only slowly adapting to the new regulations and often feel uncomfortable in prescribing due to the ongoing controversy surrounding prescriptions.

The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend the prescription of two cannabis-based medicinal products—Epidyolex and Sativex—for the treatment of four main conditions: chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, spasticity of adults with multiple sclerosis (MS), and two severe treatment-resistant epilepsies.[2] While welcomed as a move in the right direction, these guidelines have been criticized by patients, campaigners, and some doctors as being too limiting. Many question the narrow choice of recommended products and the lack of recommendation of medical cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain.[3] In stark contrast to the current NICE guidelines, people in other countries are using medical cannabis for a broad variety of indications ranging from (in order of self-reported use) pain, depression, anxiety, insomnia, arthritis, fibromyalgia, muscle spasms, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, headaches, and more.[4]

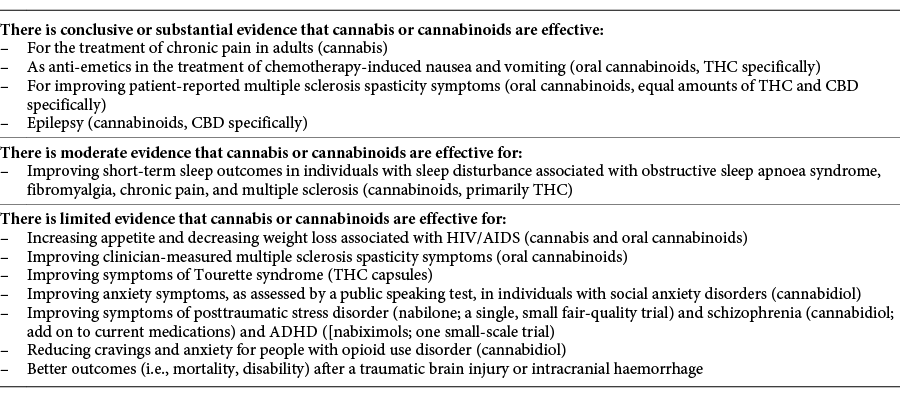

The U.S.-based National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) agrees that there is conclusive or substantial evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective for the treatment of chronic pain in adults.[5] However, further research conclusions by NASEM on the health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids highlight that despite extensive changes in global policy on medical cannabis, there is limited conclusive evidence regarding its short- and long-term health effects (both harms and benefits). Table 1 summarizes NASEM’s findings, with some recent additions.[6]

|

In contrast to the U.K., in many other countries, medical cannabis has been made available to patients in a very short space of time. This paper evaluates different medical cannabis regulatory frameworks and their resulting patient access outcomes, aiming to answer 1. how have changes in global regulatory policies resulted in appropriate access for patients at the country level, and 2. what can be learned from these policies to propose optimal regulatory mechanisms in the U.K.

Case studies of regulatory systems and patient access

To date, the regulation of medical cannabis is complex, involving many mixed approaches and grey areas. Regulatory frameworks differ greatly among countries and states, plus there is often a lack of clarity within a country regarding the specifics of the approaches and how they are applied in practice. We hope that our analysis and case studies better ensure that U.K. legislators can follow a successful regulatory path, avoiding the mistakes other countries have made.

Germany

In Germany, medical cannabis was legalized in March 2017. Today, the country is the leading medical cannabis prescriber in Europe.[7] Fourteen kinds of cannabis flowers can be prescribed for any condition if no other treatment is available, or if a standard treatment cannot be used because of potential side effects.[8] Health insurance companies can only refuse reimbursement in case of rare exemptions. So far, there are no universal criteria for insurance companies to base their compensation decisions on. As such, the German regulatory framework comprises a policy that provides broad access to medical cannabis.

Prior to legalization, medical cannabis was a niche in Germany, with only around 1,000 critically ill patients having been given special permission to use it. Since then, demand has risen rapidly—surprising government officials—leading to frequent shortages in pharmacies, with domestic production only recently starting to pick up the slack. The authors of the country's cannabis legislation estimated that only about 700 patients per year would want the prescription packs.[9] However, by September 2017 more than 12,000 patients had applied for reimbursement of their treatment with medical cannabis. In 2018, there were over 185,000 prescriptions for medicinal cannabis in Germany, with around 60,000 to 80,000 patients using medicinal cannabis products.[10]

References

- ↑ Nutt, D. (2019). "Why medical cannabis is still out of patients' reach-an essay by David Nutt". BMJ 365: l1903. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1903. PMID 31043373.

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (11 November 2019). "Cannabis-based medicinal products - NICE guideline [NG144"]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng144.

- ↑ Burns, C. (2019). "NICE recommends first cannabis-based medicines for use on the NHS". The Pharmaceutical Journal 303 (7931). doi:10.1211/PJ.2019.20207320.

- ↑ United Patients' Alliance (2018). "UPA Patients' Survey 2018". https://www.upalliance.org/patient-survey-2018.

- ↑ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017). The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/24625. ISBN 9780309453073.

- ↑ Drug Science (31 January 2019). "DrugScience Symposium 'Cannabis medicines: from principle to practice. How can we maximise clinical research and benefits?'". https://drugscience.org.uk/drugscience-symposium-cannabis-medicines-from-principle-to-practice-how-can-we-maximise-clinical-research-and-benefits/.

- ↑ Prohibition Partners (2019). "The European Cannabis Report 4th Edition". https://prohibitionpartners.com/reports/.

- ↑ Krcevski-Skvarc, N.; Wells, C.; Häuser, W. (2018). "Availability and approval of cannabis-based medicines for chronic pain management and palliative/supportive care in Europe: A survey of the status in the chapters of the European Pain Federation". European Journal of Pain 22 (3). doi:10.1002/ejp.1147. PMID 29134767.

- ↑ Dobush, G. (1 February 2019). "Why can’t Germany get its medical marijuana industry going?". Handelsblatt Today. https://www.handelsblatt.com/english/companies/cannabis-why-cant-germany-get-its-medical-marijuana-industry-going/23811676.html.

- ↑ Pascual, A. (12 June 2019). "Germany’s medical cannabis market prioritizes efficacy over unfettered access". Marijuana Business Daily. https://mjbizdaily.com/germanys-medical-cannabis-market-prioritizes-efficacy-over-unfettered-access/.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The URL to citation #4, regarding the United Patients’ Alliance 2018 Survey, is dead and is unfortunately not archived. The URL to citation #7 was also dead; a substituted URL is used in its place. Nothing else was changed in accordance with the NoDerivatives portion of the license.