Journal:An evaluation of regulatory regimes of medical cannabis: What lessons can be learned for the UK?

| Full article title | An evaluation of regulatory regimes of medical cannabis: What lessons can be learned for the UK? |

|---|---|

| Journal | Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids |

| Author(s) | Schlag, Anne K. |

| Author affiliation(s) | DrugScience, King's College |

| Primary contact | Email: anne dot schlag at kcl dot ac dot uk |

| Year published | 2020 |

| Volume and issue | 3(1) |

| Page(s) | 76–83 |

| DOI | 10.1159/000505028 |

| ISSN | 2504-3889 |

| Distribution license | Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International |

| Website | https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/505028 |

| Download | https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/505028 (PDF) |

Abstract

This paper evaluates current regulatory regimes of medical cannabis using peer-reviewed and grey literature, as well as personal communications. Despite the legalization of medical cannabis in the U.K. in November 2018, patients still lack access to the medicine, with fewer than 10 NHS prescriptions having been written to date. We look at six countries that have been at the forefront of prescribing medical cannabis, including case studies of the three largest medical cannabis markets in the European Union: Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands. Canada, Israel, and Australia add global examples. These countries have a more successful history of prescribing medical cannabis than the U.K. Their legislation is outlined and number of medical cannabis prescriptions provided to give an indication of how successful their regulatory regime has been in providing patient access. Evaluating countries’ medical cannabis regulations allows us to offer implications for lessons to be learned for the development of a successful medical cannabis regime in the U.K.

Keywords: medical cannabis, patient access, legislation, regulation

Introduction

Cannabis has a long history, being one of the oldest medicines and having been used for millennia.[1] However, today’s medical cannabis, used for a broad range of indications, only has a short past, requiring novel regulatory regimes to ensure the safe and effective use of cannabis as medicine. In most countries, the provision of medical cannabis has evolved over time, often in response to patient demand and/or product developments. International licensing laws regarding the safety and quality of cannabis medicines vary greatly.

In the U.K., medical cannabis was legalized and made available under special license through the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in November 2018 as a result of public controversy and campaigning. Nevertheless, since that time, only a very small number of patients with a limited range of conditions have been provided treatment within the National Health Service (NHS), meaning that medical cannabis remains inaccessible for most patients in need. Physicians are only slowly adapting to the new regulations and often feel uncomfortable in prescribing due to the ongoing controversy surrounding prescriptions.

The current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend the prescription of two cannabis-based medicinal products—Epidyolex and Sativex—for the treatment of four main conditions: chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, spasticity of adults with multiple sclerosis (MS), and two severe treatment-resistant epilepsies.[2] While welcomed as a move in the right direction, these guidelines have been criticized by patients, campaigners, and some doctors as being too limiting. Many question the narrow choice of recommended products and the lack of recommendation of medical cannabis for the treatment of chronic pain.[3] In stark contrast to the current NICE guidelines, people in other countries are using medical cannabis for a broad variety of indications ranging from (in order of self-reported use) pain, depression, anxiety, insomnia, arthritis, fibromyalgia, muscle spasms, irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, headaches, and more.[4]

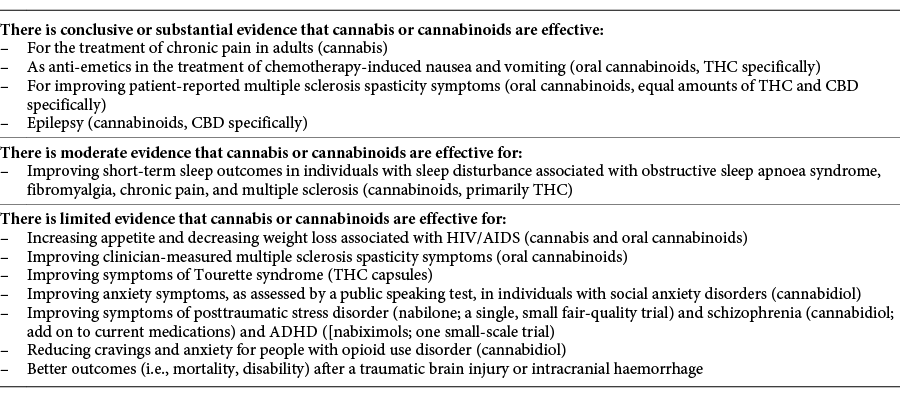

The U.S.-based National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) agrees that there is conclusive or substantial evidence that cannabis or cannabinoids are effective for the treatment of chronic pain in adults.[5] However, further research conclusions by NASEM on the health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids highlight that despite extensive changes in global policy on medical cannabis, there is limited conclusive evidence regarding its short- and long-term health effects (both harms and benefits). Table 1 summarizes NASEM’s findings, with some recent additions.[6]

|

In contrast to the U.K., in many other countries, medical cannabis has been made available to patients in a very short space of time. This paper evaluates different medical cannabis regulatory frameworks and their resulting patient access outcomes, aiming to answer 1. how have changes in global regulatory policies resulted in appropriate access for patients at the country level, and 2. what can be learned from these policies to propose optimal regulatory mechanisms in the U.K.

Case studies of regulatory systems and patient access

To date, the regulation of medical cannabis is complex, involving many mixed approaches and grey areas. Regulatory frameworks differ greatly among countries and states, plus there is often a lack of clarity within a country regarding the specifics of the approaches and how they are applied in practice. We hope that our analysis and case studies better ensure that U.K. legislators can follow a successful regulatory path, avoiding the mistakes other countries have made.

Germany

In Germany, medical cannabis was legalized in March 2017. Today, the country is the leading medical cannabis prescriber in Europe.[7] Fourteen kinds of cannabis flowers can be prescribed for any condition if no other treatment is available, or if a standard treatment cannot be used because of potential side effects.[8] Health insurance companies can only refuse reimbursement in case of rare exemptions. So far, there are no universal criteria for insurance companies to base their compensation decisions on. As such, the German regulatory framework comprises a policy that provides broad access to medical cannabis.

Prior to legalization, medical cannabis was a niche in Germany, with only around 1,000 critically ill patients having been given special permission to use it. Since then, demand has risen rapidly—surprising government officials—leading to frequent shortages in pharmacies, with domestic production only recently starting to pick up the slack. The authors of the country's cannabis legislation estimated that only about 700 patients per year would want the prescription packs.[9] However, by September 2017 more than 12,000 patients had applied for reimbursement of their treatment with medical cannabis. In 2018, there were over 185,000 prescriptions for medicinal cannabis in Germany, with around 60,000 to 80,000 patients using medicinal cannabis products.[10]

Despite the stark increase in patient numbers, doctors are still often reluctant to prescribe medicines containing cannabis because of the hurdles they face in its approval by health insurance companies, and because there is still some stigma about the use of cannabis, even for medical purposes. Moreover, doctors lack continuing education about the drug, and are, thus, often both skeptical about its medical effects as well as concerned about potential risks. To date, there are no “medical cannabis” modules or courses at universities or higher education institutions (per personal communication with J. Witte, July 2019).

Likely because of its rapid introduction and uptake, medical cannabis remains a controversial topic for many physicians in Germany. The fact that cannabis prescriptions are permitted without the same level of efficacy requirements needed for other prescription medications has incurred the wrath of physicians in Germany.[11] Consequently, a group of associations representing the German medical community has recently appealed to the medical community, journalists, insurers, and politicians to adopt a “more responsible” approach toward medical cannabis.[12]

Italy

After Germany, Italy has the highest number of medical cannabis prescriptions in the E.U. Since 2006, doctors in Italy can prescribe “masterly preparations” by pharmacists in the pharmacy, using either Dronabinol or a plant-based active substance based on cannabis for medical use. The active substance can be obtained from cannabis cultivated under authorization of a national organization for cannabis. It can be taken in the form of decoction or by inhalation with a special vaporizer. Since 2013, neurologists have also been able to prescribe Sativex for spasticity and MS-related pain. Sativex was classified for the purpose of supply as a medicinal product, subject to a restrictive medical prescription by a specialist, which could subsequently be renewed.

Five cannabis flowers (Bedrocan, Bediol, Bedica, Bedrobinol, and Bedrolite)—and Aurora products in the future—can be prescribed for spasticity-associated pain and other chronic pain conditions. Palliative care conditions are nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapeutic agents and radiation therapy, HIV therapy cachexia, and anorexia in patients with cancer and AIDS, all only if refractory to conventional treatment.[8] Doctors should prescribe the most appropriate genetic strain, dispensing amount, and consumption method for each patient. There is full reimbursement by Italian health authorities. At the end of January 2019, 26,042 prescriptions, attributed to 12,998 unique patients, were registered on the AIFA database.[13]

The Netherlands

Dutch law has permitted doctors to prescribe medical cannabis since 2003. The cannabis flowers Bedrocan, Bediol, Bedica, Bedrobinol, and Bedrolite can be prescribed by any physician for disorders with associated spasticity in combination with pain (e.g., from MS, spine damage) and any other types of chronic pain. Palliative care symptoms to control are nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy or radiotherapy in cancer; HIV combination therapy and medication in hepatitis C infection; palliative cancer treatment, and AIDS symptoms (e.g., loss of appetite and weight, pain, nausea).[8]

The Office for Medicinal Cannabis (OMC), founded in March 2000, is the government office responsible for the production of cannabis for medical and scientific purposes and for the supply to pharmacies, universities, and research institutes. Under the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the OMC has the exclusive right of importing and exporting cannabis, cannabis extracts, and cannabis resin. The Convention provides for this monopoly so as to prevent the diversion of cannabis into the black market.

Cannabis is widely available due to the liberal recreational cannabis policy in the Netherlands. Around half a million people use cannabis for medical purposes, many of those without a prescription.[14] However, this may not be a reliable estimate (per personal communication with W. Scholten, July 2019).

Prior to 2003, medical cannabis users often felt stigmatized by having to go to a coffee shop; but if delivered by a pharmacy, cannabis is just a “medicine” without the negative connotations of recreational drug use. The price per gram is around €10 in a coffee shop and around €6 in a pharmacy, making the latter a more financially viable option for patients, and ensuring that the quality of their medical cannabis meets pharmaceutical requirements (per personal communication with W. Scholten, July 2019).

Summary of other countries' legislation and patient access policies

In addition to the above European case studies, globally, an ever increasing number of countries can provide useful examples of how to implement successful medical cannabis regimes. The present list is by no means exhaustive; rather it is meant to provide a variety of approaches to learn from.

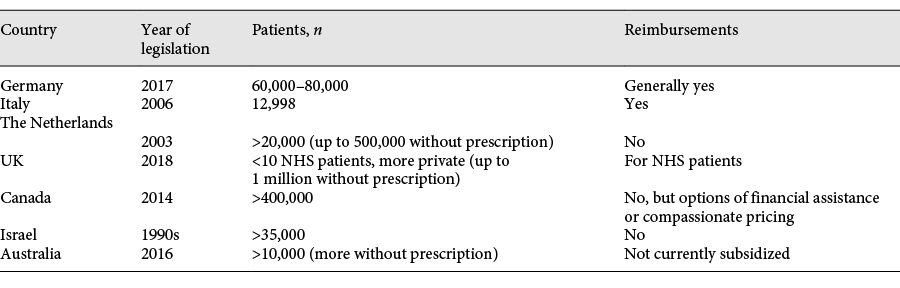

Table 2 provides an overview showing year of legislation, patient numbers, and whether medical cannabis is reimbursed by health insurance companies for the previous three E.U. countries and the U.K., as well as Canada, Israel, and Australia (detailed further below). Patient numbers of each country can provide an initial indication of the effectiveness of a particular country’s regulatory regime.

|

Canada

Canada was one of the earliest adapters to medical cannabis. Legal access to dried cannabis was first allowed in 1999 through discretionary exemptions granted by the Minister of Health for medical or scientific purposes or in the public interest. In April 2014, a legislative change allowed for full legalization of medical cannabis production. At this time, there were 7,914 patients registered in Health Canada’s database. As of the end of September 2018, there were 342,103 patients registered, with over 400,000 patients registered to date.[15]

Israel

As one of the first countries outside North America to allow the prescription of medical cannabis, Israel issued the first medical cannabis licenses in the 1990s following legal petitions of individual patients to the Supreme Court. Within two decades, the number of licensed patients has increased exponentially, and the number of licenses is currently estimated to be above 35,000. Health insurance companies do not cover the cost of cannabis.

The Israel Medical Cannabis Agency is a special regulatory agency within the Ministry of Health providing detailed criteria for a wide list of indications that cannabis can be authorized for. In April 2019, the Health Ministry was receiving 300 applications per day from patients requesting personal licenses for medical cannabis use, with a huge backlog awaiting approval.[16]

Australia

A later adaptor, Australia's legalization of medical cannabis was enabled by the Narcotic Drugs Amendment Act 2016, which permits research, cultivation, and production of medicinal cannabis and related products. Corresponding amendments were also made to the Therapeutic Goods Act 1989 to facilitate regulatory approvals and special access schemes for unapproved medicinal cannabis products. At present, medical cannabis is not subsidized.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved Special Access Scheme applications for medicinal cannabis for a broad range of indications. By May 31, 2019, the Therapeutic Goods Administration had approved over 7,700 applications for medicinal cannabis products, with new approval requests increasing rapidly: in August 2019 alone, there were 2,893 new medical cannabis approvals.[17][18] Nevertheless, the number of patients currently receiving products is relatively small compared to the number thought to be using illicit cannabis products for medical purposes.

Lessons the U.K. can learn

The variety of existing regulatory approaches highlights the need to clarify medical cannabis regulatory frameworks and their applications in practice. Although most countries are still working in a trial-and-error situation, they can offer important lessons to be learned for the successful implementation of a medical cannabis regime in the U.K.

Education, training, and support for physicians and health care professionals

The lack of education and training for medical cannabis practitioners has limited the application of medical cannabis treatments across much of Europe. Consequently, physicians’ further education and the continuing development of guidelines for prescribing (reviewed in tandem with new scientific evidence) is key.

There is a need to develop and distribute a registered accreditation and education platform that provides training on treatable symptoms, registered products, and the therapeutic effects of different cannabinoids, dosages, and application procedures. Since there has been a lack of medical cannabis education by the U.K. government so far, this information vacuum has been filled by various non-governmental organizations. The Academy of Medical Cannabis provides a free 12-module program on the basics of cannabis, which has been used by over 1,000 doctors. Drug Science launched a similar online resource, MEDIC, and arranges regular, free seminars for health care professionals (HCPs).

Medical cannabis training is required for medical students in higher education so that future prescribers become familiar with the medicine. Fully accredited university courses ensure not only the development of specialists but also of the medical cannabis field per se, providing a recognized academic basis. This is currently provided in Israel and Italy, and it is important that the U.K. follows this lead.[19] Drug Science has developed medical cannabis modules to be included in U.K. universities so that relevant experts can be fully trained and readily available to prescribe and advise patients as required.[20] Further developments should include a diverse range of other teaching possibilities, especially accredited certificate course programs.

Physicians also need to be supported in order to feel more comfortable in prescribing medical cannabis. Potential concerns by physicians when deciding if and how to prescribe medical cannabis need to be addressed urgently so the medicine can reach patients in need. Regulators might benefit from being involved in training to get an in-depth understanding of both the risks and benefits involved. This might include direct access to a government-funded online help platform to ask questions, such as the New South Wales Cannabis Medicines Advisory Service.[21]

In order to counterbalance the relatively strict guidelines by NICE, as well as those published by the Royal College of Physicians (for pain and nausea) and by the British Paediatric Neurology Association (for childhood epilepsy), the Medical Cannabis Clinicians Society has published more balanced guidelines. By reference to all these guidelines, U.K. physicians can now make a more balanced decision on medical cannabis prescription with the best interests of their patient in mind.

Improving the evidence base through real-world data collection

There is the need for more data to develop the current scientific evidence base. So far, there is no homogenous way of data collection on medical cannabis patients and the number of prescriptions written across countries. In Canada, the development of a large-scale database allows for side-effects to be monitored and managed more effectively. Results can then be incorporated to develop regulation and policy-making. Ideally, doctors should develop the evidence base (including case studies) together with their patients to better define indications. Areas which have significant data gaps will still require more rigorous studies and randomized control trials (RCTs).

The collection of safety data is essential. Doctors and other HCPs need to be able to monitor the outcome of any treatment. Adverse effects must be registered and addressed, e.g., through the yellow card system in the U.K. For many medical cannabis-prescribing countries, this data still needs to be collected, analyzed, and made available in order to build up a reliable database of medical cannabis use, involving number of prescriptions, benefits, and risks. The TWENTY/21 project launched by Drug Science in November 2019 aims to contribute to this longitudinal goal.

The Cancer Drugs Fund as an example of a "managed access" program

The Cancer Drugs Fund can provide a model for medical cannabis.[22] According to its “managed access” program, if NICE sees a drug as promising but there is not enough evidence on the drug’s benefits and value for money to recommend that the NHS routinely pay for it, NICE can approve the drug for a limited time and have it paid for via the Cancer Drugs Fund while more evidence is gathered. In this way, many patients can be prescribed drugs that would not otherwise have been available, giving them new options and renewed chances of successful treatment. The fund also collects data on efficacy and safety, along with patient reported outcomes, for the patients who are prescribed them. NICE then makes a final decision once that limited time is up, often using evidence of any benefit the drug has provided to NHS patients to help inform that decision.

Establishing a medical cannabis office

A special medical cannabis government office (as in the Netherlands and Israel) can ensure responsible production of cannabis for medical and scientific purposes and for the supply to pharmacies, universities, and research institutes. If medical cannabis is produced and distributed in commission by the government to ensure quality and patient safety, patients are able to receive the medical cannabis they require, developed to pharmaceutical grade standards and grown by certified growers.

Addressing transparency concerning industry relationships

It is vital to address concerns about possible conflicts of interest and biases when working with the medical cannabis industry or conducting industry-funded work. Publications should require authors to acknowledge a link to the medical cannabis industry, as is already the case for alcohol and tobacco. Any industry involvement has to be transparent and freely available in order to build and maintain the public’s and physicians’ trust. Aggressive marketing approaches by the industry have already backfired in Germany and need to remain prohibited in the U.K., as they would likely increase the stigma associated with medical cannabis.

Importance of effectively calculating demand

It is vital to conduct an exact calculation of the actual demand and a feasible market plan of how this demand can be met. Since the U.K. already is the world’s largest producer and exporter of legal cannabis for medical and scientific uses, it needs to be ensured that it can provide U.K. patients as well. The right providers have to be in place to avoid shortfalls in the medicines, as has been the case in Germany.

Clarifying costs and insurance

Costs should be covered by the NHS (as well as private insurance companies) so that medical cannabis can be available to all patients who could benefit from it. As costs to patients can be high, health insurance companies need to be able to make positive recommendations, despite the current lack of RCTs. Costs for legal medical cannabis need to be kept lower than black-market costs to avoid patients having to revert to the latter for financial reasons.

Doctors are still often reluctant to prescribe medicines containing cannabis because of the hurdles they face in its approval by health insurance companies. In order to have a more objective regulation and insurance, as well as more homogenous assessments, it is important to have universal criteria for insurance companies to base their decisions on. Insurers need to develop standardized and binding guidelines around the criteria used to approve or deny cannabis treatment reimbursements.

Involving patients and addressing patient concerns

It is essential to communicate with the public, addressing the issues they are worried about and that they need to know about, such as who will pay for treatment, what products are available, and for which indications, highlighting that medical cannabis might not work in every case. This ensures that expectations are realistic and that doctors are not burdened with having to deal with an aggravated public. When discussing treatment options, risks and benefits of medical cannabis, as well as alternatives, need to be clarified to patients. Individual assessments need to be made for each patient, and opportunities for patient contact have to be regular and ongoing. Prescribers need to be well prepared and confident with the prescribing process. This process should be kept as straightforward as possible to avoid doctors being deterred by any additional regulatory burden.

Addressing communication among stakeholders

Policy makers and regulators need to address areas of uncertainty and focus on further developing the science as well as regulations. Patient groups (representing different indications) need to be well represented, taken seriously, and actively involved in decision-making. There is a need for ongoing stakeholder communication involving all interested parties in order to foster a relationship of trust that can help to avoid public controversy.

Addressing stigma

Medical cannabis is still often stigmatized due to its association with recreational use. It is vital to decrease stigma to gain further acceptance by the medical establishment so that its benefits can be fully realized. Prescriptions are increasingly adding credibility and respectability to medical cannabis. The more prescriptions written, the more people are likely to view cannabis as a medicine rather than associate it with a recreational drug. The example of the Netherlands shows that pharmacies and other official providers are essential to reducing stigma, both for prescribers and patients alike. Rather than consuming a black-market product, in this way, patients can be provided with a fully regulated medical product, without the negative connotations of recreational cannabis.

Addressing the role of the media

Media interactions are vital. It is important to address medical controversies in a timely and efficient manner, making sure that both favorable and opposing views are included in decision-making. It needs to be ensured that the media presents both sides of the story, rather than focusing on sensationalist negatives (putting the public off) or false positives (fostering false hopes). Information originating from industry tends to be perceived as biased by the public and physicians alike. As such, journalists need to conduct careful research, verify the quality of their data, and ensure unbiased information sources. Industry involvement has to be transparent and clear in order to build and maintain the public’s and physicians’ trust.

Conclusions

The variety of approaches to medical cannabis regulation and their resulting patient access outcomes highlight the benefits, as well as shortcomings, of different regulatory regimes. Globally, countries take different approaches, reflecting various historical and cultural factors. While it is yet too early to conclude on the “optimal approach” that should be adopted by all, valuable lessons can be learned by the U.K. Despite differences in their regulatory approaches to medical cannabis, all countries agree on the need for continued education for physicians and other HCPs. Furthermore, it is important to streamline policy-making and improve communications between policy makers, physicians, and patients. Collaborations between these stakeholders need to be strengthened so that international networks to effectively evaluate and regulate medical cannabis can be build.

Regulations need to be developed in a timely and efficient manner. If this is neglected, it creates a vacuum of regulation, which will be filled from other interest groups, such as industry and lobbying groups. In the U.S., the lack of a regulatory system (e.g., regarding the dispensing of medical cannabis) coupled with aggressive industry marketing has led to a “free–for-all scenario” in many states, which has not been conducive to patients’ wellbeing or to the further development of scientific evidence. Supervision of pharmacy activities carried out by local health authorities can add an extra layer of control. If regulation, on the other hand, is too conservative, it will fuel the illicit market with all the risks this entails. It is important to have an adequate regulatory mechanism in place now, which can be developed and improved in tandem with political and scientific developments. There is a need to develop guidelines and regulations that can be followed, which are neither too strict nor too broad.

Today, medical cannabis policy and research is developing rapidly in line with shifting public attitudes. The regulatory challenges explored highlight the complexity of decision-making about medical cannabis. Additionally, to further high-quality studies to investigate the current uncertainties in scientific evidence, the global regulation of medical cannabis requires a dialogue among stakeholders in order to develop regulatory frameworks and their application in practice for the best way forward. In contrast to many other countries, in the U.K., the current procedures to access medical cannabis are not working. By understanding other countries’ learnings and implementing them in policy-making, it is hoped that the introduction of medical cannabis in the U.K. can finally proceed in a way that maximizes clinical research and patient benefit, ensuring that the medicine can reach patients in need.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Peyman Adjamian provided background information on Italy, Israel, and Australia. Prof. David Nutt reviewed the initial manuscript.

Funding

No additional funding was received for the writing of this paper.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Anne Katrin Schlag is Head of Research of the charity Drug Science. Drug Science has a Medical Cannabis Working Group, which is supported by an unrestricted educational grant by a consortium of medical cannabis industry partners.

References

- ↑ Nutt, D. (2019). "Why medical cannabis is still out of patients' reach-an essay by David Nutt". BMJ 365: l1903. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1903. PMID 31043373.

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (11 November 2019). "Cannabis-based medicinal products - NICE guideline [NG144"]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng144.

- ↑ Burns, C. (2019). "NICE recommends first cannabis-based medicines for use on the NHS". The Pharmaceutical Journal 303 (7931). doi:10.1211/PJ.2019.20207320.

- ↑ United Patients' Alliance (2018). "UPA Patients' Survey 2018". https://www.upalliance.org/patient-survey-2018.

- ↑ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017). The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/24625. ISBN 9780309453073.

- ↑ Drug Science (31 January 2019). "DrugScience Symposium 'Cannabis medicines: from principle to practice. How can we maximise clinical research and benefits?'". https://drugscience.org.uk/drugscience-symposium-cannabis-medicines-from-principle-to-practice-how-can-we-maximise-clinical-research-and-benefits/.

- ↑ Prohibition Partners (2019). "The European Cannabis Report 4th Edition". https://prohibitionpartners.com/reports/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Krcevski-Skvarc, N.; Wells, C.; Häuser, W. (2018). "Availability and approval of cannabis-based medicines for chronic pain management and palliative/supportive care in Europe: A survey of the status in the chapters of the European Pain Federation". European Journal of Pain 22 (3). doi:10.1002/ejp.1147. PMID 29134767.

- ↑ Dobush, G. (1 February 2019). "Why can’t Germany get its medical marijuana industry going?". Handelsblatt Today. https://www.handelsblatt.com/english/companies/cannabis-why-cant-germany-get-its-medical-marijuana-industry-going/23811676.html.

- ↑ Pascual, A. (12 June 2019). "Germany’s medical cannabis market prioritizes efficacy over unfettered access". Marijuana Business Daily. https://mjbizdaily.com/germanys-medical-cannabis-market-prioritizes-efficacy-over-unfettered-access/.

- ↑ Lutzhöft, N.; Hart, C. (June 2019). "Investing in the future of cannabis in the UK - lessons from the German model". Bird & Bird. https://www.twobirds.com/en/news/articles/2019/uk/investing-in-the-future-of-cannabis-in-the-uk--lessons-from-the-german-model.

- ↑ Häuser, W.; Hoch, E.; Petzke, F. et al. (17 April 2019). "Medizinalcannabis und cannabisbasierte Arzneimittel: Ein Appell an Ärzte, Journalisten, Krankenkassen und Politiker für einen verantwortungsvollen Umgang" (PDF). https://mjbizdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/20190417_Appell_Medizinalhanf_und_Cannabisbasierte_Arzneimittel.pdf.

- ↑ Da Cas, R.; Salvi, E.; Menniti-Ippolito, F. (2019). "P-25 Use and Safety of Cannabis for Medical Use in Italy - The 2nd International Annual Congress on Controversies on Cannabis-Based Medicines (Med-Cannabis 2019)". Medical Cannabis and Cannabinoids 2: 69–83. doi:10.1159/000500623.

- ↑ van Laar, M.W.; van Gestel, B.; Cruts, A.A.N. et al., ed. (2017) (PDF). Nationale Drug Monitor. Trimbos Institute. ISBN 9789052537771. https://www.trimbos.nl/docs/f8502344-4a38-4a87-9740-bc408805e2fa.pdf.

- ↑ Government of Canada (29 August 2019). "ARCHIVED – Market data under the Access to Cannabis for Medical Purposes Regulations". Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medication/cannabis/licensed-producers/market-data.html.

- ↑ Lidman, M. (2 April 2019). "Medical cannabis reform leaves at least 5,000 patients with no medicine". The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/medical-cannabis-reform-leaves-at-least-5000-patients-with-no-medicine/.

- ↑ Therapeutic Goods Administration (2020). "Accessing unapproved products - Medicinal cannabis". Australian Government. https://www.tga.gov.au/node/769199.

- ↑ Lamers, M. (23 September 2019). "Proposed overhaul of Australia’s medical cannabis framework ‘far too slow,’ industry officials say". Marijuana Business Daily. https://mjbizdaily.com/proposed-overhaul-of-australias-medical-cannabis-framework-far-too-slow-industry-officials-say/.

- ↑ Halon, E. (8 July 2019). "Israeli college to offer degree specializing in medical cannabis". The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Israeli-college-to-offer-degree-specializing-in-medical-cannabis-594948.

- ↑ Drug Science (11 September 2019). "Medical Cannabis Education". https://www.drugscience.org.uk/medical-cannabis-education/.

- ↑ New South Wales Ministry of Health (July 2018). "NSW Cannabis Medicines Advisory Service" (PDF). New South Wales Government. https://www.medicinalcannabis.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/2493/NSW-Cannabis-Medicines-Advisory-Service-Fact-Sheet_FINAL.pdf.

- ↑ Sim, D. (14 December 2018). "The new Cancer Drugs Fund has quietly reached a significant milestone". Cancer Research UK Science Blog. https://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2018/12/14/the-new-cancer-drugs-fund-has-quietly-reached-a-significant-milestone/.

Notes

This presentation is faithful to the original, with only a few minor changes to presentation. Some grammar and punctuation was cleaned up to improve readability. In some cases important information was missing from the references, and that information was added. The URL to citation #4, regarding the United Patients’ Alliance 2018 Survey, is dead and is unfortunately not archived. The URL to citation #7 was also dead; a substituted URL is used in its place. At least one inline URL was turned into a formal citation. Nothing else was changed in accordance with the NoDerivatives portion of the license.